All this was enabled by the existence of a flexible system of governmental control that was intimately connected with the religion and the economics of the society and one that gave power to both the people and the leaders of the kingdoms.

The key political unit on which government was based in all the Yoruba kingdoms was the town, ilu . Each kingdom consisted of many towns but this did not mean that there were many independent governments in each kingdom. What happened was that the government of the capital served as the central government of the kingdoms, while those of the subordinate towns served as local governments units.

Whether at the central or local level, the system of government was monarchical; that is, it was headed by an oba , or king. The oba of a particular town or kingdom had a specific title, usually peculiar to him. Thus we have titles as the Oni of Ife, the Alaafin of Oyo, the Alake of Ake (later Abeokuta ), etc…

The Oba had enormous powers of authority having the power of life or death over his subjects and was, as a king not accountable to them for any of his acts.In practice however, the oba was not an absolute ruler. It is true that as the executive head of the government he exercised considerable powers particular over the common people. He could arrest, punish or even behead them without trial. But these were powers that he had to exercise sparingly and more with justification than without it. In any event the powers of the oba was checked in number of ways. To begin with he did not rule his twon or kingdom alone. He did so together with his council known as the igbimo. The igbimo of each town usually consisted of the most senior chiefs, who were themselves usually representatives of certain lineages, that is, descent groups in the town bound together by strong family or kinship ties. The igbimo was a body that the oba had to consult. He could not make any laws or take any decisions on matters fundamentally affecting the town without the concurrence of the igbimo. If he did, or if he became an oppressive leader in any other way, the consequences were usually grave.

The manner in which the oba was dealt with was often formalized in a unwritten constitution. The best known example was that of Old Oyo, the capital of the Old Oyo Empire. There the igbimo (called Oyo Mesi), could reject an Alaafin who acted improperly or became an oppressive ruler. The sentence of rejection which was often pronounced by the Basorun and head of the Oyo Mesi on behalf of his collegues ran thus; ‘The gods reject you, earth rejects, the people reject you.' Any Alaafin thus rejected had to commit suicide.

The oba was also kept in check by religious duties and taboos. The Yoruba people believed that the general well-being of the community depended on the amount of favour bestowed upon them by Heaven through supernatural beings, the orisa (deities) and the ancestors. Misfortunes and general crisis like famine or an epidemic were taken to be an index of the anger of these supernatural beings. The deities and ancestors were constantly propitiated by means of sacrifices and festivals were held in their honour. It was the duty of the oba to see that these festivals were observed and necessary sacrifices made. In addition, the priests, through whom these gods consulted, often prescribed taboos which the oba had to obey. There is evidence that priests in collusion with both the chiefs and the people would impose certain taboos in order to check despotism. All this show that there was no room for unfettered despotism in the political system of the Yoruba up to 1800.

Administratively and judicially, each town was divided into a number of wards or quarters known generally as adugbo at the head of which was the ijoye (chief). An adugbo was made of a number of compounds. Each compound was headed by a baale or olori ebi (head of the compound or head of the extended family). The ijoye had a specific title and his appointment must confirmed or approved by the oba whereas that of baale was an informal title. The gradation in the administrative and judicial systems of the town government in Yoruba kingdoms meant that there was many functionaries in the system. The effect was the government was not far removed from the people and vica-versa. Indeed, the people regarded the government as their government. Consequently, the people were ready to support the oba, his chiefs and other government functionaries as long as they operated according to the established norms. The communal spirit exhibited in supporting the oba's government was a symbol of function of the communal spirit that permeated the society. Public works, like the making of roads and paths or the building of afara (bridges) were done communally. At family and lineage levels, the policy of being one's brother's keeper was also pursued. The result was that the social problems like the ones common in present-day society, hardly existed for the government to tackle. The overall result was that there was peace, order and stability in most of Yorubaland up to 1800.

The Golden Age

This effective administrative foundation enabled many Yoruba societies to flourish. Their agricultural economies as well as their textile industries bloomed. The system of agriculture was so successful that the people not only had enough for their consumption but they also had a large quantity for internal and external trade. The same more or less applied to the early cloth weaving industries in Yorubaland. The cloth produced by the various types of looms were of a very high quality and were very sought after by merchants and traders alike.

There were also one or two simple industries that sprung from this period of stability in the region. The iron and smelting industries were perhaps the most important of these. Iron workers produced the iron which blacksmiths used in the making of agricultural implements and the tools used in other industries.

Another major result of the stability of the Yoruba society was the development of the religion which formed an important part in the life of the Yoruba people. The essence of this religion was in the belief of one supreme being which they called Olodumare or Olorun. They believed that Olodumare had control over their life's and the general well-being of the community. But all this depended on the amount of favour that he bestowed on them. In order to have his favour, man must struggle to the will of Olodumare. This however could only be done through the intervention of the orisa's and dead ancestors. The proliferation of the orisa often makes those ignorant of their functions think that the Yoruba served many gods. In fact, their ultimate belief was in Olodumare, the supreme being. As a by product of this religion, the Yoruba had norms which regulated their social life, and which gave them a high standard of morality. Their religion demanded that doing the will of Olodumare involved not just worshiping and making sacrifices as dictated by the orisa through the preists, but also living a morally sound life. Consequently, the Yoruba feared violating moral laws, particularly in their dealings with their fellow human beings.

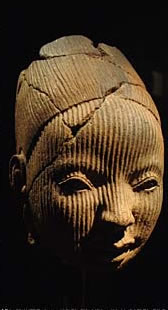

With peace, order and stability in their society, it was possible for the Yoruba to utilise their leisure profitably. Part of the result was an outstanding achievement in the works of art, the greatest evidence of which was found at Ile-Ife. But apart from Ile-Ife, evidence of this achievement has been found by archaeologists at Old Oyo, Ilesa and Owo. This creativity still exists among the Yoruba till this day and it often finds various avenues of expression even though the Golden Age as long since melted in to the fabric of time. Hopefully such times will again return to the Forest Kingdoms and the artistry and creativity of these peoples will one day again be given the freedom it truly deserves.

Back to Top

|